In this tutorial, we’ll be using Django to create an online service that shows visitors their current weather and location. We’ll develop the service and host it using repl.it.

To work through this tutorial, you should ideally have basic knowledge of Python and some knowledge of web application development. However, we’ll explain all of our reasoning and each line of code thoroughly , so if you have any programming experience you should be able to follow along as a complete Python or web app beginner too. We’ll also be making use of some HTML, JavaScript, and jQuery, so if you have been exposed to these before you’ll be able to work through more quickly. If you haven’t, this will be a great place to start.

To display the weather at the user’s current location, we’ll have to tie together a few pieces. The main components of our system are:

The main goals of this tutorial are to: * Show how to set up and host a Django application using repl.it. * Show how to join existing APIs together to create a new service.

By using this tutorial as a starting point, you can easily create your own bespoke web applications. Instead of showing weather data to your visitors, you could, for example, pull and combine data from any of the hundreds of APIs found at this list of public APIs.

You won’t need to install any software or programming languages on your local machine, as we’ll be developing our application directly through repl.it. Head over there and create an account.

Press the + button in the top right to create a new project and search for “Django Template”. Give your project a name and press “Create repl”.

By default, Django comes with a pretty complicated folder structure of existing files and folders. There’s also a README.md file that will open by default, giving you some guidance on how to find your way around.

We won’t explain what all these different components are for and how they tie together in this tutorial. If you want to understand Django better, you should go through their official tutorial.

In this tutorial, we’ll just look at the few files that we need to modify to get our basic application working.

Hit the Run button in the bar at the top and you’ll see Repl.it install all of the required packages and start up the default Django app.

Viewing the default website isn’t that interesting and you’ll notice that there are no files containing the content you currently see, so you can’t easily modify it.

To create our own page in place, we’ll have to modify several files. If you’ve created a basic HTML file before, you might be surprised at how complicated this step is. Like other frameworks, Django “makes the easy things hard, and the hard things possible”. If you just want to display a basic web page, it’s probably over kill, but as your web app grows, you’ll find use for all of the extra structure.

Let’s set up a basic “Hello world” page to make sure we have the pieces in place. You’ll need to create several more folders and files to achieve this.

Create a folder called templates. This is where Django will get HTML templates for rendering pages.

Let’s add the HTML templates that we will use to render our static page. Create a file called base.html within the newly created templates folder and add the following code.

{% load static %}

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Hello World!</title>

<meta charset="UTF-8"/>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1"/>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{% static "css/style.css" %}">

</head>

<body>

{% block content %}{% endblock content %}

</body>

</html>The above is a basic HTML template that our Django app will use when rendering pages. We also link to a stylesheet that Django will get from a folder called static/css which we will create soon. Note the {% load static %} in the first line, this is to tell Django that we are using static files in this template ie. style.css.

Still in the templates folder, create a file called index.html and add the following code.

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<h1>Hello World!</h1>

{% endblock content %}This is a file written in Django’s template language, which often looks very much like HTML (and is usually found in files with a .html extension), but which contains some extra functionality to help us load dynamic data from the back end of our web application into the front end for our users to see.

The above extends the base.html template and adds the block content to it, in this case “Hello World!”.

Django looks for template folders within “app” folders by default. This is helpful when you have multiple apps within your project but in this case we don’t so we need to tell Django where to find our templates folder.

Open the mysite/settings.py file, scroll down to TEMPLATES and add os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'templates') within the square brackets next to DIRS: like below

'DIRS': [os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'templates')],

Now that we have our templates added, let’s add the folders and files for adding the stylesheet.

Create a folder called static and also create a folder called css within the static folder.

Create a file called style.css within the static/css/ directory and add the following code.

body {

background-color: lightblue;

}

h1 {

color: navy;

margin-left: 20px;

}Above we add basic CSS code to demonstrate how you can modify the look of your site.

Django handles static files similar to templates where it automatically checks app directories for a directory called static. Since we only have a static page instead of apps we need to tell Django where our static directory is located.

Open the mysite/settings.py file, scroll all the way down and add the following code right after STATIC_URL ='/static/'

STATICFILES_DIRS = (os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'static'),)

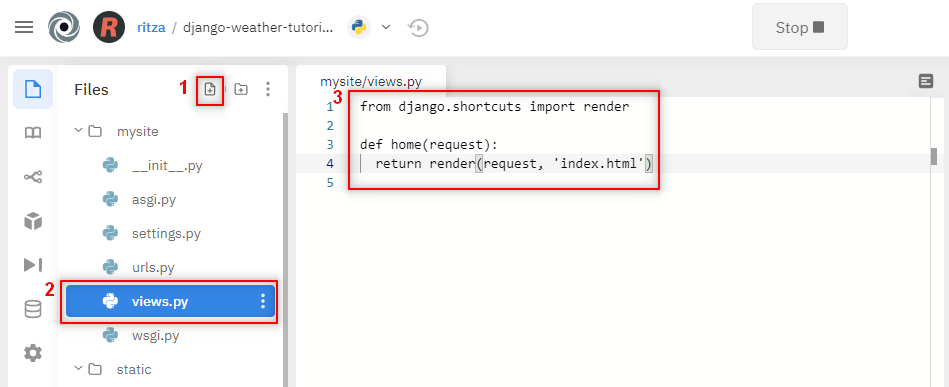

Within the mysite/ directory, create a file called views.py and add the following code.

from django.shortcuts import render

# Create your views here.

def home(request):

return render(request, 'index.html')A view function in Django is a Python function that takes Web requests and returns a Web response. This is where you add the logic that will return a certain response when called. In our case we define a view that will return the index.html page.

To call this view function we need to add it to our url patterns. Open the mysite/urls.py file and replace the contents with the below code.

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.home, name= 'home'),

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

]Note that we import the views file created earlier from . import views. Then we add the url pattern with an empty path '' and point it to the home view created earlier. The admin/ path points to the admin page that comes as a default with Django.

When Django receives a request it goes through the urlpatterns list until it finds a match. In our case <url>.com will match the first path and return the home view that will render the index.html page. If we navigate to<url>.com/admin/, Django will match the pattern of the admin/ path and return the admin page.

Restart your server and refresh the web page on the right. You should see our “Hello World!” page.

Great, we have now put all the pieces in place for our “Hello World!” web page.Let’s expand this and start building our weather app.

Open the templates/index.html file and change the code where it says “Hello World!” to read “Weather” like below.

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<h1>Weather</h1>

{% endblock content %}Click the refresh button as indicated below to see the result change from “Hello World!” to “Weather”.

You can also press the pop-out button to the right of the the URL bar to open only the resulting web page that we’re building, as a visitor would see it. You can share the URL with anyone and they’ll be able to see your Weather website already!

Changing the static text that our visitors see is a good start, but our web application still doesn’t do anything. We’ll change that in the next step by using JavaScript to get our user’s IP Address.

An IP address is like a phone number. When you visit “google.com”, your computer actually looks up the the name google.com to get a resulting IP address that is linked to one of Google’s servers. While people find it easier to remember names like “google.com”, computers work better with numbers. Instead of typing “google.com” into your browser toolbar, you could type the IP address 216.58.223.46, with the same results. Every device connecting to the internet, whether to serve content (like google.com) or to consume it (like you, reading this tutorial) has an IP address.

IP addresses are interesting to us because it is possible to guess a user’s location based on their IP address. (In reality, this is an imprecise and highly complicated process, but for our purposes it will be more than adequate). We will use the web service ipify.org to retrieve our visitors’ IP addresses.

In the Repl.it files tab, navigate to templates/base.html, which should look as follows.

{% load static %}

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Hello World!</title>

<meta charset="UTF-8"/>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1"/>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{% static "css/style.css" %}">

</head>

<body>

{% block content %}{% endblock content %}

</body>

</html>The “head” section of this template is between lines 5 and 11 – the opening and closing <head> tags. We’ll add our scripts directly below the <link ...> on line 10 and above the closing </head> tag on line 11. Modify this part of code to add the following lines:

<script>

function use_ip(json) {

alert("Your IP address is: " + json.ip);

}

</script>

<script src="https://api.ipify.org?format=jsonp&callback=use_ip"></script>These are two snippets of JavaScript. The first (lines 1-5) is a function that when called will display a pop-up box (an “alert”) in our visitor’s browser showing their IP address from the json object that we pass in. The second (line 7) loads an external script from ipify’s API and asks it to pass data (including our visitor’s IP address) along to the use_ip function that we provide.

If you open your web app again and refresh the page, you should see this script in action (if you’re running an adblocker, it might block the ipify scripts, so try disabling that temporarily if you have any issues).

This code doesn’t do anything with the IP address except display it to the user, but it is enough to see that the first component of our system (getting our user’s IP Address) is working. This also introduces the first dynamic functionality to our app – before, any visitor would see exactly the same thing, but now we can show each visitor something related specifically to them (no two people have the same IP address).

Now instead of simply showing this IP address to our visitor, we’ll modify the code to rather pass it along to our Repl webserver (the “backend” of our application), so that we can use it to fetch location information through a different service.

Currently our Django application only has two routes, the default (admin/) route and our home route (/) which is loaded as our home page. We’ll add another route at /get_weather_from_ip where we can pass an IP address to our application to detect the location and get a current weather report.

To do this, we’ll need to modify the files at mysite/views.py and mysite/urls.py.

Edit urls.py to look as follows (add line 8, but you shouldn’t need to change anything else).

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.home, name=home),

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

path('get_weather_from_ip/', views.get_weather_from_ip, name="get_weather_from_ip"),

]We’ve added a definition for the get_weather_from_ip route, telling our app that if anyone visits https://django-weather-tutorial-eugenedorfling.ritza.repl.co/get_weather_from_ip then we should trigger a function in our views.py file that is also called get_weather_from_ip. Let’s write that function now.

In your views.py file, add a get_weather_from_ip() function beneath the existing home() one, and add an import for JsonResponse on line 2. Your whole views.py file should now look like this:

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import JsonResponse

# Create your views here.

def home(request):

return render(request, 'index.html')

def get_weather_from_ip(request):

print(request.GET.get("ip_address"))

data = {"weather_data": 20}

return JsonResponse(data)By default, Django passes a request argument to all views. This is an object that contains information about our user and the connection, and any additional arguments passed in the URL. As our application isn’t connected to any weather services yet, we’ll just make up a temperature (20) and pass that back to our user as JSON.

In line 10, we print out the IP address that we will pass along to this route from the GET arguments (we’ll look at how to use this later). We then create the fake data (which we’ll later replace with real data) and return a JSON response (the data in a format that a computer can read more easily, with no formatting). We return JSON instead of HTML because our system is going to use this route internally to pass data between the front and back ends of our application, but we don’t expect our users to use this directly.

To test this part of our system, open your web application in a new tab and add /get_weather_from_ip?ip_address=123 to the URL. Here, we’re asking our system to fetch weather data for the IP address 123 (not a real IP address). In your browser, you’ll see the fake weather data displayed in a format that can easily be programmatically parsed.

In our Repl’s output, we can see that the backend of our application has found the “IP address” and printed it out, between some other outputs telling us which routes are being visited and which port our server is running on:

The steps that remain now are to:

Let’s start by using Ajax to pass the user’s IP address that we collected before to our new route, without our user having to explicitly visit the get_weather_from_ip endpoint or refresh their page.

We’ll use Ajax through jQuery to do a “partial page refresh” – that is, to update part of the page the user is seeing by sending new data from our backend code without the user needing to reload the page.

To do this, we need to include jQuery as a library.

Note: usually you wouldn’t add JavaScript directly to your base.html template, but to keep things simpler and to avoid creating too many files, we’ll be diverging from some good practices. See the Django documentation for some guidance on how to structure JavaScript properly in larger projects.

In your templates/base.html file, add the following script above the line where we previously defined the use_ip() function.

<script

src="https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.3.1.min.js"

integrity="sha256-FgpCb/KJQlLNfOu91ta32o/NMZxltwRo8QtmkMRdAu8="

crossorigin="anonymous"></script>

This loads the entire jQuery library from a CDN, allowing us to complete certain tasks using fewer lines of JavaScript.

Now, modify the use_ip() script that we wrote before to call our backend route using Ajax. The new use_ip() function should be as follows:

function use_ip(json) {

$.ajax({

url: {% url 'get_weather_from_ip' %},

data: {"ip": json.ip},

dataType: 'json',

success: function (data) {

document.getElementById("weatherdata").innerHTML = data.weather_data

}

});

}Our new use_ip()function makes an asynchronous call to our get_weather_from_ip route, sending along the IP address that we previously displayed in a pop-up box. If the call is successful, we call a new function (in the success: section) with the returned data. This new function (line 7) looks for an HTML element with the ID of weatherdata and replaces the contents with the weather_data attribute of the response that we received from get_weather_from_ip (which at the moment is still hardcoded to be “20”).

To see the results, we’ll need to add an HTML element as a placeholder with the id weatherdata. Do this in the templates/index.html file as follows.

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<h1>Weather</h1>

<p id=weatherdata></p>

{% endblock %}This adds an empty HTML paragraph element which our JavaScript can populate once it has the required data.

Now reload the app and you should see our fake 20 being displayed to the user. If you don’t see what you expect, open up your browser’s developer tools for Chrome and Firefox) and have a look at the Console section for any JavaScript errors. A clean console (with no errors) is shown below.

Now it’s time to change out our mock data for real data by calling two services backend – the first to get the user’s location from their IP address and the second to fetch the weather for that location.

The service at ip-api.com is very simple to use. To get the country and city from an IP address we only need to make one web call. We’ll use the python requests library for this, so first we’ll have to add an import for this to our views.py file, and then write a function that can translate IP addresses to location information. Add the following import to yourviews.py file:

import requestsand above the get_weather_from_ip() function, add theget_location_from_ip() function as follows:

def get_location_from_ip(ip_address):

response = requests.get("http://ip-api.com/json/{}".format(ip_address))

return response.json()Note: again we are diverging from best practice in the name of simplicity. Usually whenever you write any code that relies on networking (as above), you should add exception handling so that your code can fail more gracefully if there are problems.

You can see the response that we’ll be getting from this service by trying it out in your browser. Visit http://ip-api.com/json/41.71.107.123 to see the JSON response for that specific IP address.

Take a look specifically at the highlighted location information that we’ll need to extract to pass on to a weather service.

Before we set up the weather component, let’s display the user’s current location data instead of the hardcoded temperature that we had before. Change the get_weather_from_ip() function to call our new function and pass along some useful data as follows:

def get_weather_from_ip(request):

ip_address = request.GET.get("ip")

location = get_location_from_ip(ip_address)

city = location.get("city")

country_code = location.get("countryCode")

s = "You're in {}, {}".format(city, country_code)

data = {"weather_data": s}

return JsonResponse(data)Now, instead of just printing the IP address that we get sent and making up some weather data, we use the IP address to guess the user’s location, and pass the city and country code back to the template to be displayed. If you reload your app again, you should see something similar to the following (though hopefully with your location instead of mine).

That’s the location component of our app done and dusted – let’s move on to getting weather data for that location now.

To get weather data automatically from OpenWeatherMap, you’ll need an API Key. This is a unique string that OpenWeatherMap gives to each user of their service and it’s used mainly to restrict how many calls each person can make in a specified period. Luckily, OpenWeatherMap provides a generous “free” allowance of calls, so we won’t need to spend any money to build our app. Unfortunately, this allowance is not quite generous enough to allow me to share my key with every reader of this tutorial, so you’ll need to sign up for your own account and generate your own key.

Visit openweathermap.org, hit the “sign up” button, and register for the service by giving them an email address and choosing a password. Then navigate to the API Keys section and note down your unique API key (or copy it to your clipboard).

This key is a bit like a password – when we use OpenWeatherMap’s service, we’ll always send along this key to indicate that it’s us making the call. Because Repl.it’s projects are public by default, we’ll need to be careful to keep this key private and prevent other people making too many calls using our OpenWeatherMap quota (potentially making our app fail when OpenWeatherMap starts blocking our calls). Luckily Repl.it provides a neat way of solving this problem using .envfiles.

In your project, create a new file using the “New file” button as shown below. Make sure that the file is in the root of your project and that you name the file .env (in Linux, starting a filename with a . usually indicates that it’s a system or configuration file). Inside this file, define the OPEN_WEATHER_TOKEN variable as follows, but using your own token instead of the fake one below. Make sure not to have a space on either side of the = sign.

OPEN_WEATHER_TOKEN=1be9250b94bf6803234b56a87e55f

Repl.it will load the contents of this file into our server’s environment variables. We’ll be able to access this using the os library in Python, but when other people view or fork our Repl, they won’t see the .env file, keeping our API key safe and private.

To fetch weather data, we need to call the OpenWeatherMap api, passing along a search term. To make sure we’re getting the city that we want, it’s good to pass along the country code as well as the city name. For example, to get the weather in London right now, we can visit (again, you’ll need to add your own API key in place of the string after appid=) https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=London,UK&units=metric&appid=cb932829eacb6a0e9ee4f382a2a56734b39

To test this, you can visit the URL in your browser first. If you prefer Fahrenheit to Celsius, simply change the unit=metric part of the url to units=imperial.

Let’s write one last function in our views.py file to replicate this call for our visitor’s city which we previously displayed.

First we need to add an import for the Python os (operating system) module so that we can access our environment variables. At the top of views.py add:

import osNow we can write the function. Add the following to views.py:

def get_weather_from_location(city, country_code):

token = os.environ.get("OPEN_WEATHER_TOKEN")

url = "https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q={},{}&units=metric&appid={}".format(

city, country_code, token)

response = requests.get(url)

return response.json()In line 2, we get our API key from the environment variables (note, you sometimes need to refresh the repl.it page with your repl in to properly load in the environment variables), and we then use this to format our URL properly in line 3. We get the response from OpenWeatherMap and return it as json.

We can now use this function in our get_weather_from_ip() function by modifying it to look as follows:

def get_weather_from_ip(request):

ip_address = request.GET.get("ip")

location = get_location_from_ip(ip_address)

city = location.get("city")

country_code = location.get("countryCode")

weather_data = get_weather_from_location(city, country_code)

description = weather_data['weather'][0]['description']

temperature = weather_data['main']['temp']

s = "You're in {}, {}. You can expect {} with a temperature of {} degrees".format(city, country_code, description, temperature)

data = {"weather_data": s}

return JsonResponse(data)We now get the weather data in line 6, parse this into a description and temperature in lines 7 and 8, and add this to the string we pass back to our template in line 9. If you reload the page, you should see your location and your weather.

Because we’re doing several API calls now, the page might be blank for a few seconds after loading before populating the weather and location data. Again, if you don’t see what you expect, check the Repl.it server output and have a look at your browser’s developer tools console.

You now have a basic Django application that can be visited by anyone and which shows dynamic data.

If you want to extend the application, Repl.it makes it easy to “fork”, which means you’ll be able to clone the Repl exactly where we left off and modify it any way you want. Simply head over to my Repl at https://repl.it/@ritza/django-weather-tutorial-eugenedorfling and hit the “Fork” button. If you didn’t create an account at the beginning of this tutorial, you’ll be prompted to create one. (You can even use a lot of Repl functionality without creating an account.)

If you’re stuck for ideas, some possible extensions are:

In the next tutorial, we’ll be looking at building our own CRM app with NodeJS and Repl.it. This tutorial will also introduce you to setting up a MongoDB database and creating a user interface. You can also find more tutorials like this one here.